Master: Each motion in tai chi must be done with purpose and intent

By Julie Halm

Tai chi is a practice that looks very graceful when done correctly, but according to a local expert cannot be thought of as a dance of any kind.

“There is a rule not to be violated that every move in tai chi should be good for both health and martial art applications,” said Sifu James Roach (“sifu” is a Chinese word that means teacher). “After all, the real benefit of tai chi is the development of ‘neigong’ or, in English, ‘internal discipline’ in the body and not a fancy dance routine.”

Roach is a master certified teacher in classical tai chi instruction and has been a practitioner of the martial art for more than four decades. He teaches at Buffalo State.

He initially became interested in tai chi after experiencing some karate instruction in the U.S. Marine Corps. He was drawn to the internal aspect of the practice and eventually began to study under Stephen Hwa Ph.D., prominent tai chi master.

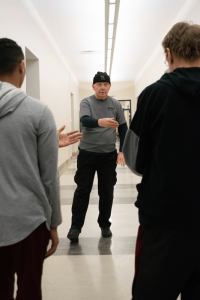

In attending one of Roach’s classes, held at Buffalo State College, a first-timer might think that the moves do not look overly-complicated. As a teacher, Roach is quick to show his pupils how subtle differences in how those moves are executed make all the difference in their benefit to the body and the fulfillment of their intent. Each motion in tai chi must be done with purpose and intent, or else the value of the move is lost.

There are many forms of tai chi, which share some roots, but they have variations in their modern practices.

Noreen Starr practices at the Taoist Tai Chi Society of Buffalo. The form taught at the society is based in the traditional yang form of tai chi, but was adapted by Master Moy Lin Shin when he emigrated from Hong Kong to Canada.

The Buffalo-based nonprofit organization does not focus its practice as strongly on the martial arts aspect of tai chi, according to Starr.

“Ours is not taught for martial arts purposes,” she said. “The main focus is health purposes in the way we teach it.”

Starr, who is now almost 70, first heard of tai chi in her final year of college. By the time she decided to drop in on a class, however, many years had gone by and she was experiencing some health issues.

“I had fibromyalgia. I was getting to the point where walking was becoming almost impossible,” she said.

But practicing tai chi has changed that entirely for Starr.

“One of the big events post-tai chi was the first time I was able to go upstairs or downstairs one foot at a time,” she said.

Starr noted that individuals with a range of ailments have found relief through practicing tai chi. She mentioned people suffering from Parkinson’s disease, scoliosis and some back issues have benefited from practice tai chi. For Starr, she has also experienced increased peace of mind, calmness and a reduction in anxiety levels.

Roach agrees that the benefits can be numerous, but that tai chi is not a magic bullet of any kind.

“There are mental and physical benefits with the caveat that ‘tai chi gives back what you put into it,’” said Roach. “I have been doing it for 40-plus years and I have experienced improved joint health, internal organ health, more energy and much more but with another caveat ‘it is not a panacea.’”

Roach describes tai chi as a treasure chest of sorts, the benefits of which must be uncovered.

In that treasure chest lies the understanding of the concept of “Yi,” the martial art intent of the practice, according to Roach.

“It is single-minded and somewhat intuitive with the desire to deliver the internal power externally through hands, arm and foot, whatever the movement is. If the hand is moving forward, then the yi goes to the palm and fingers,” says Roach. “If the hand is moving laterally in a blocking movement, then the yi goes to the leading edge on the side of the hand, etc. Once the practitioner masters the yi, it is no long a conscious effort anymore. It becomes subconscious and comes naturally whenever the practitioner makes a move.”

For Starr, part of the riches she has found in practicing Taoist tai chi is simply the community, which it has brought her.

“It’s possibly the most laid back and accepting community I’ve met in my life,” she said.

That tai chi community is made up of volunteer instructors, which, according to Starr, want to bring the benefits of tai chi to as many as possible. As a result, the Buffalo chapter offers classes focused on pain reduction twice a week, which are free to the public. Instructors help people of all different physical capabilities modify the movements to their own needs.

“Tai chi does not cure anything,” she said. “But it makes a lot of things better.”

For more information on Taoist Tai Chi of Buffalo, visit www.taoisttaichi.org/locations/buffalo-center. For more information on Classical Tai Chi of Buffalo, visit www.classicaltaichiofbuffalo.com.